The process that led up to the national park idea is complex. From arts and literature came the Romantic movement, which encouraged the experience of the mountains and wilderness.

Authors like Henry Davia Thoreau and Washington Irving exhorted Americans to pursue nature even as the frontier rolled away from them. Landscape artists culminating with Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt presented awesome spectacles that received huge public interest.

The rise of attention to nature coincided with the search for identity and pride among Americans. When compared to Europe’s thousands of years of history, its fabric of ancient structures and sites, its rich cultural legacy built on many centuries of interchange, the United States appeared a rude, uncultured backwater.

Stung by caustic criticism and snobbery from Europe, Americans looked for elements in their own land to flaunt. In Yellowstone and Yosemite, and indeed the whole western wilderness, Americans had what they needed. America was new, rugged, spectacular, and could be proud of its splendor and its clean state upon which to develop the human experience.

Yet another motive for national parks came from the American experience at Niagara Falls. The famous falls were America’s paramount scenic wonder during the first half of the nineteenth century; however, local landowners had, in their frenzy to maximize profits, gone so far as to erect fences and charge viewers to look through holes at the spectacle.

The gateway arch at Yellowstone. 1900.

Tawdry concessions and souvenirs, filth, and squalor attended a visit to this most sublime of eastern American features. Clearly, government control of such a feature to assure its availability to the public was in order.

The first movement to create a park came amidst the Civil War. Yosemite Valley had been first entered by Americans chasing a band of Indians in 1851. Within five years the situation at Niagara Falls began to repeat itself.

Claims on the valley lands were filed and tolls charged. Haphazard tourism began even as the fame of the valley spread to a wondering and suspicious East.

Concern for this amazing spectacle and its availability to all comers led Congress to withdraw the lands from alienation in 1864 and turn over the valley and a nearby grove of giant sequoias to the state of California as a public park.

The state would continue to manage the first federal withdrawal of the park until 1906 when it was merged with Yosemite National Park.

Eight years later Congress established the world’s first true national park. Instrumental in its creation was the Northern Pacific Railroad, beginning a fifty-year period during which railroads became the most profound influence on the establishment of these reserves and on the development of tourism in them.

President Theodore Roosevelt pays a visit to Yellowstone. 1903.

Where the Yosemite withdrawal consisted of a pair of relatively small areas, Yellowstone was an enormous tract of more than 3,400 square miles. The creation of Yellowstone National Park marked the first serious challenge of the culture of land alienation and consumptive use in American history.

The Yellowstone withdrawal was so massive and, to many land users apparently purposeless that it was another eighteen years before a second successful park was created.

By the end of the century still, only five national parks existed, three of them in California; however, Congress was not idle in its preservation efforts and in forming reserves that would later become part of the national park system.

While early emphasis had been on the creation of National Parks, there was another movement seeking to preserve the cliff dwellings, pueblo ruins, and early missions throughout the west and southwest.

Often local ranchers would try to protect these ruins from plunder, but pot-hunters vandalized many sites. The effort began in Boston and spread to Washington, New York, Denver, and Santa Fe, during the 1880s and 1890s.

President Theodore Roosevelt addresses a crowd at the entrance to Yellowstone National Park. 1903.

In 1906, the early spate of preservation efforts culminated with the Antiquities Act which was designed to protect antiquities and objects of scientific interest in the public domain.

It authorized the President, “to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest” that existed on public lands in the United States.

The Act declared these sites to be National Monuments. It prohibited the excavation or removal of objects on Federal land unless a permit had been issued by the appropriate department.

Forty-four years after the establishment of Yellowstone, President Woodrow Wilson created the National Park Service on August 25, 1916. Today, the National Park System has grown to include 418 natural, historical, recreational, and cultural areas throughout the United States, its territories, and island possessions.

These areas include National Parks, National Monuments, National Memorials, National Military Parks, National Historic Sites, National Parkways, National Recreation Areas, National Seashores, National Scenic Riverways, and National Scenic Trails.

A member of a government geological survey stands next to Old Faithful in Yellowstone, two years before its designation as a National Park. 1870.

Tourists look out over the Grand Canyon. 1900.

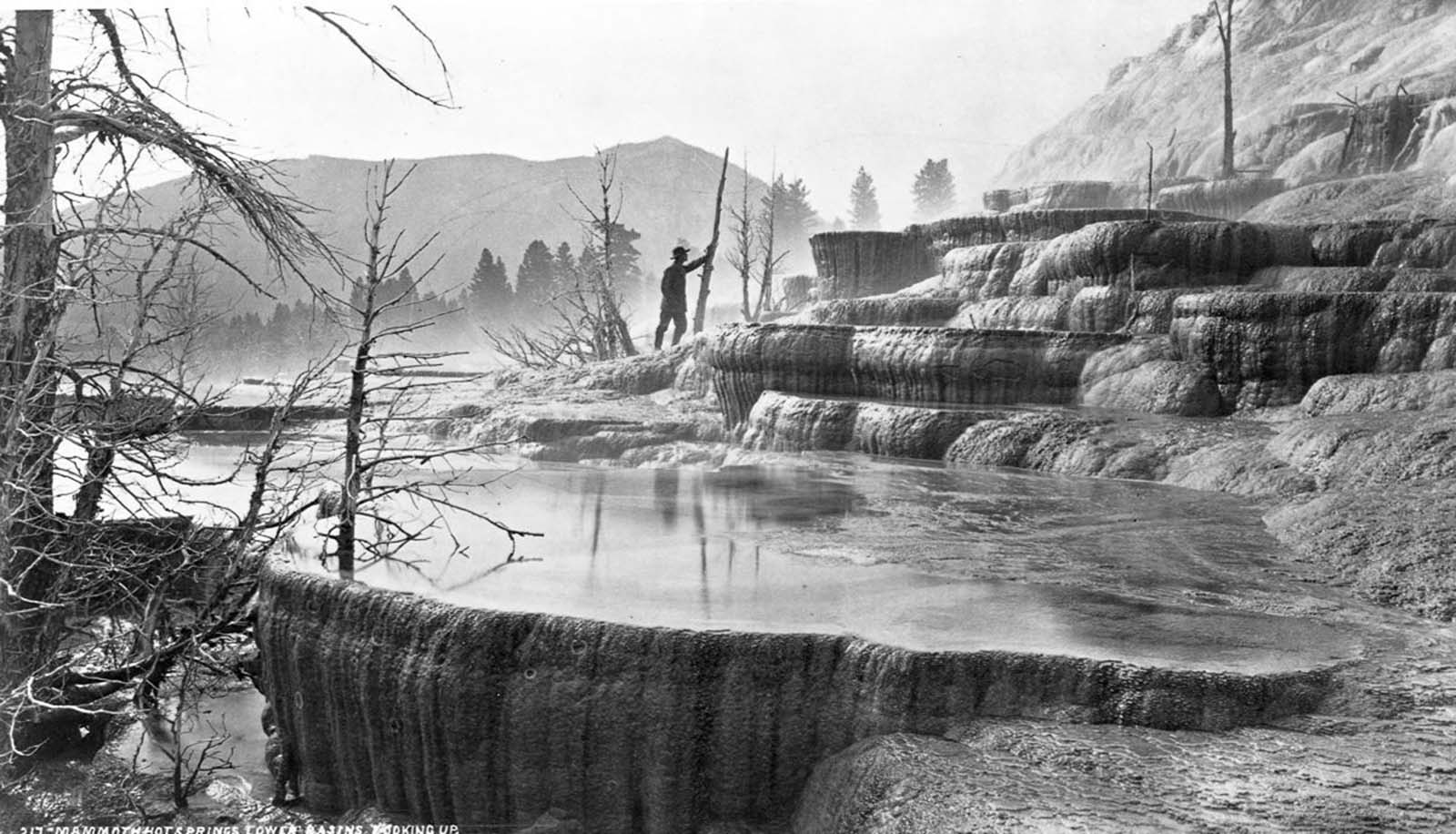

A geological surveyor explores the lower basin of Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone. 1870.

Tourists peer over a cliff into the Grand Canyon. 1880.

The Annie, reportedly the first boat ever launched on Yellowstone Lake. 1871.

Tourists drive their car on a dirt road along the Yellowstone River. 1899.

The Geyser Basins at Yellowstone. 1900.

Tourists skate on a frozen lake in Yosemite. 1910.

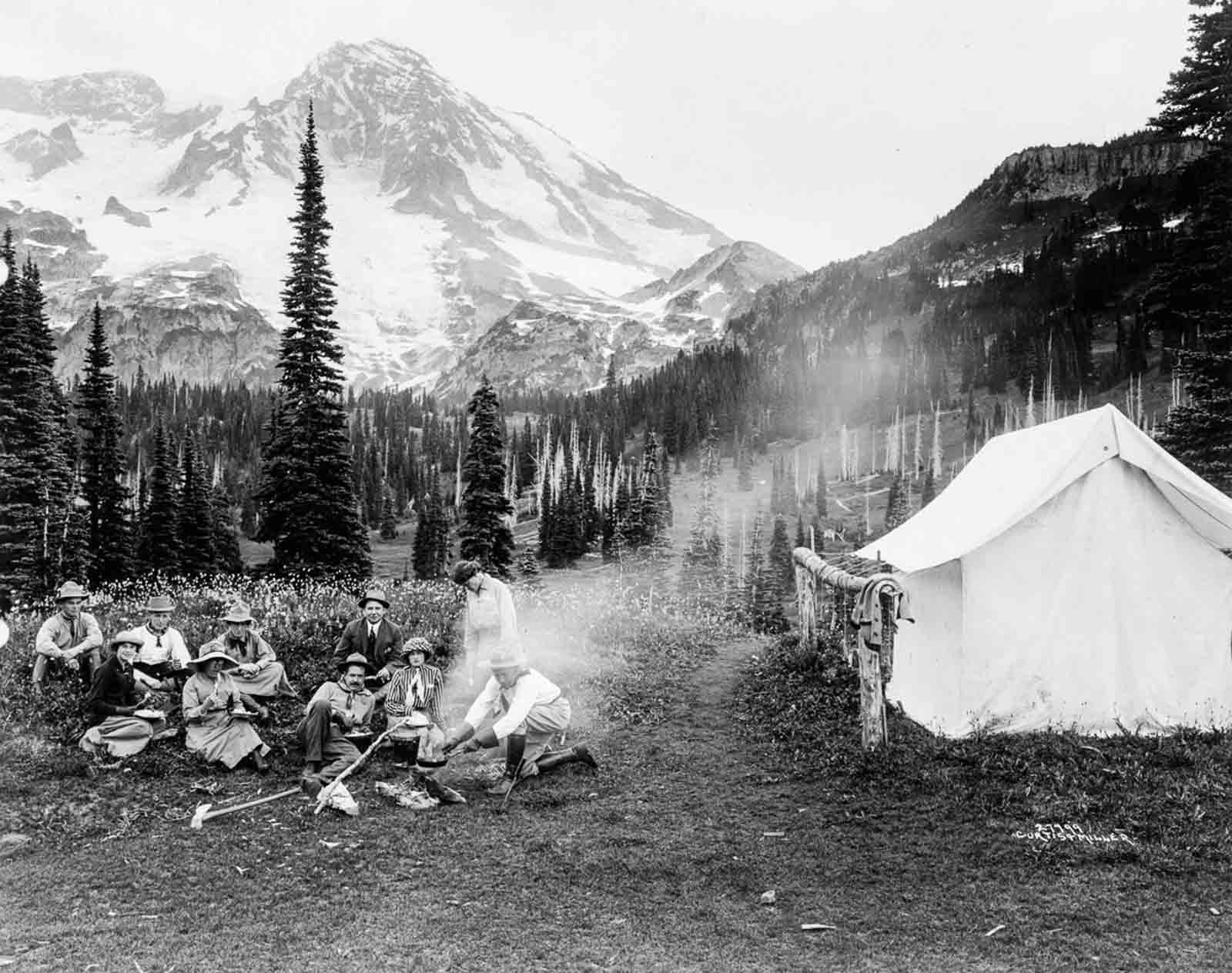

A party of tourists in Mt. Rainier National Park. 1911.

Tourists ride through Mt. Rainier National Park. 1909.

Tourists and guides picnic in Yellowstone. 1903.

Tourists ride up a trail in Rocky Mountain National Park. 1909.

Tourists boat across Crater Lake. 1912.

Tourists climb Paradise Glacier in Mt. Rainier National Park. 1911.

Tourists watch the scalding water from the Excelsior Geyser flow into the Firehole River in Yellowstone. 1917.

Tourists ride through Yosemite. 1900.

A wild elk near Tower Falls in Yellowstone. 1907.

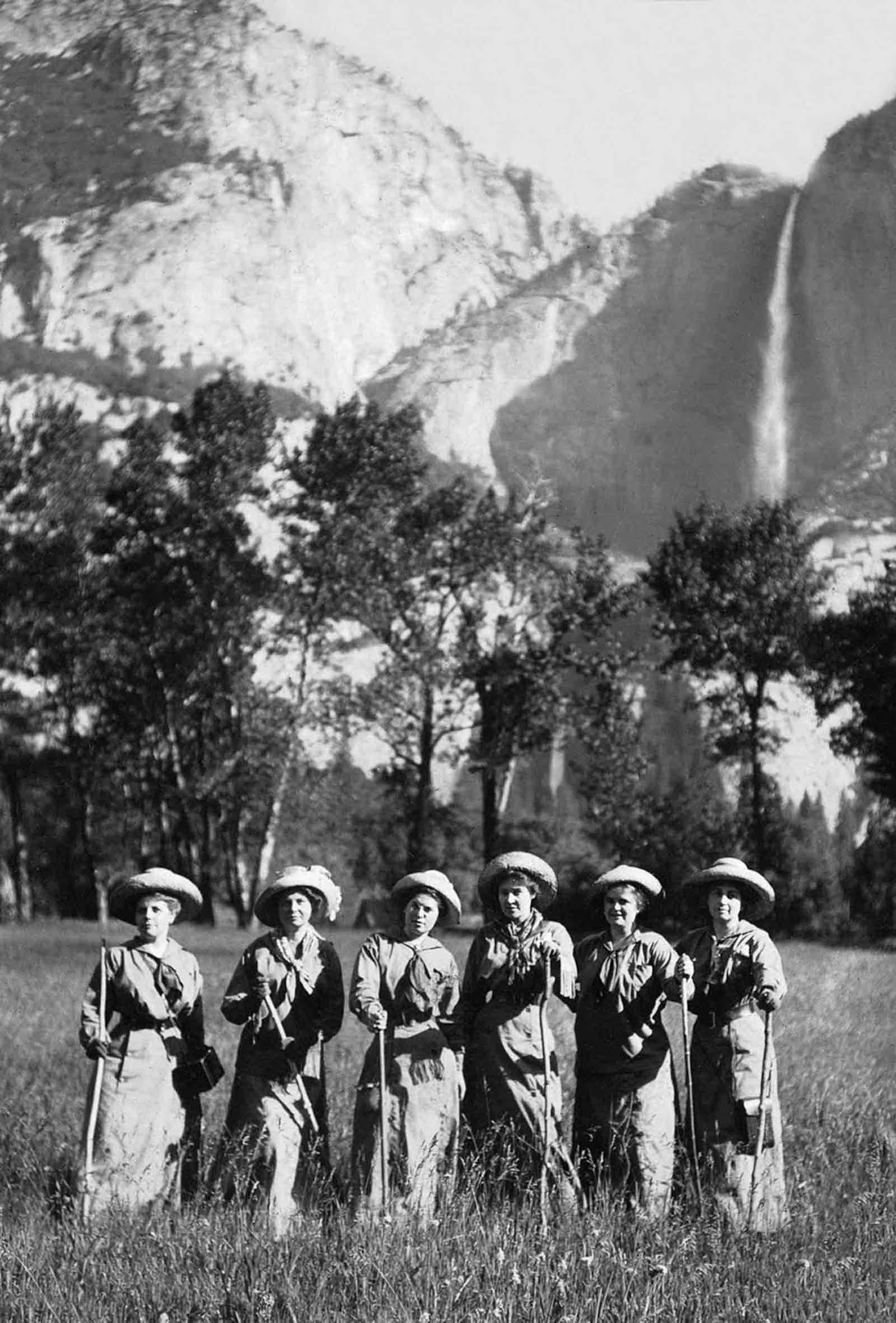

Tourists pose for a picture in front of Yosemite Falls. 1900.

A group of Yosemite tourists and their guide. 1900.

Tourists slide down a slope in Yosemite. 1903.

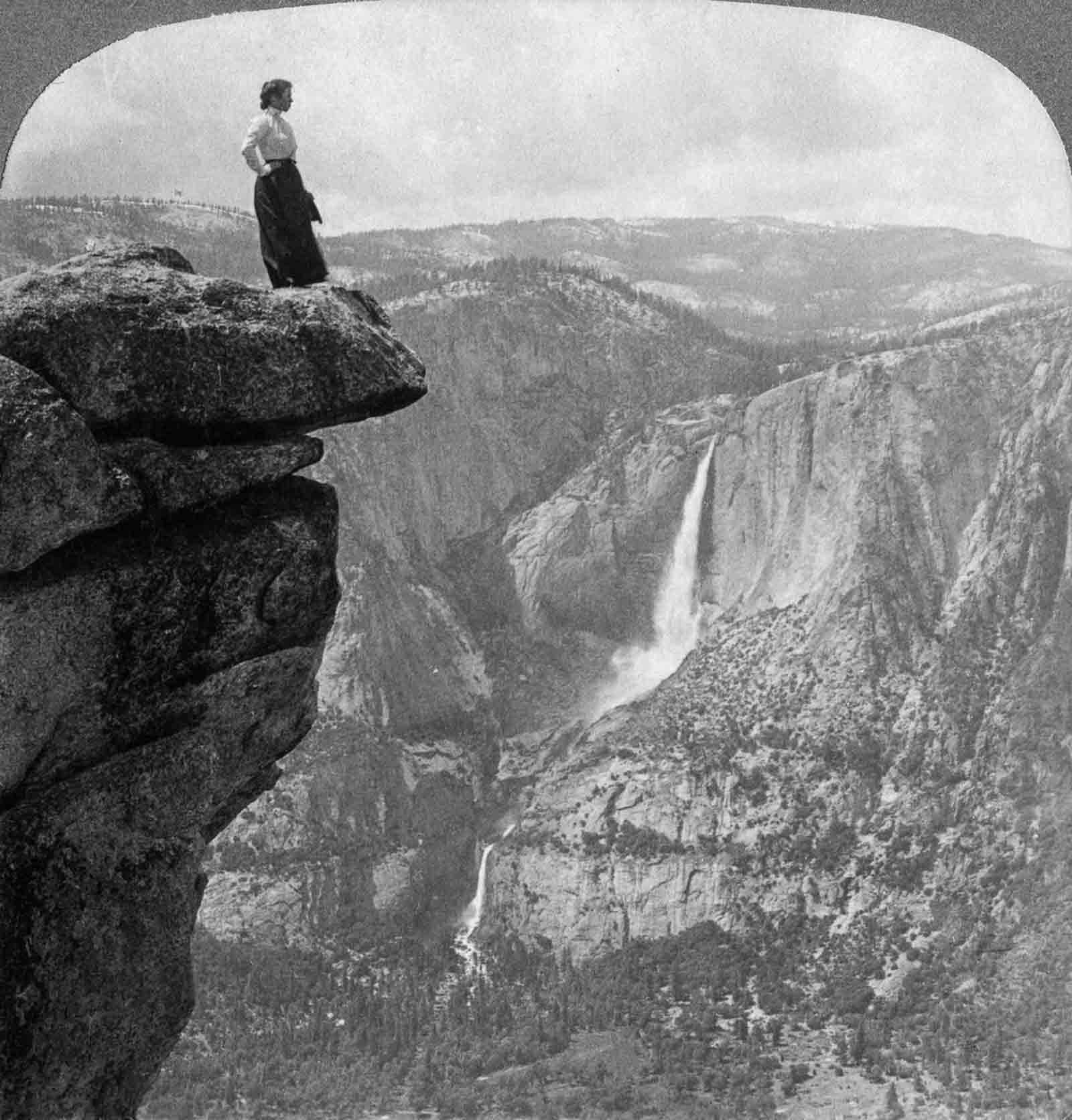

A tourist stands on Glacier Point with Yosemite Falls in the background. 1902.

Tourists ride the Glacier Point trail in Yosemite. 1901.

Tourists at Old Faithful in Yellowstone. 1901.

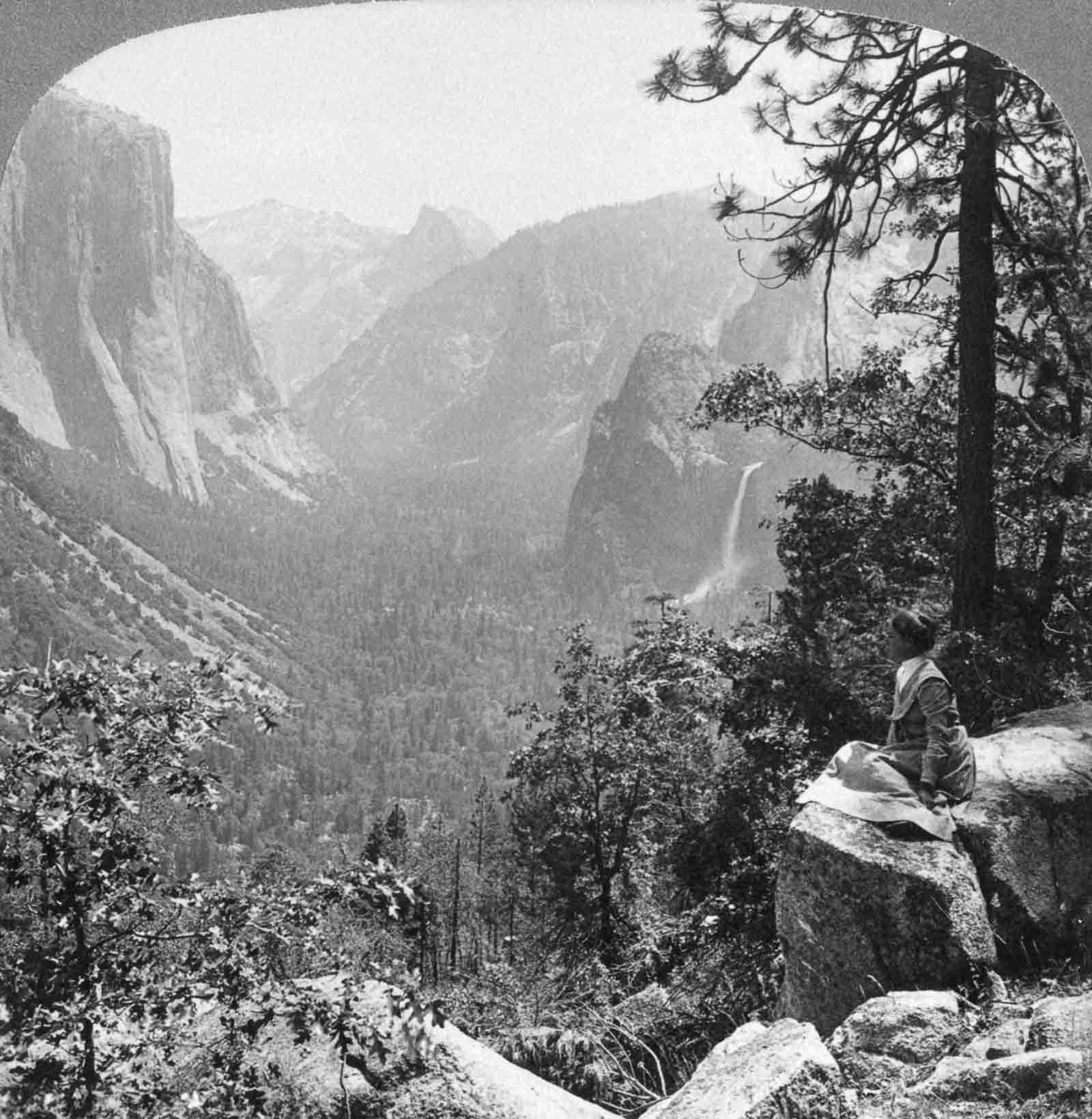

The view of Yosemite Valley from Inspiration Point. 1902.

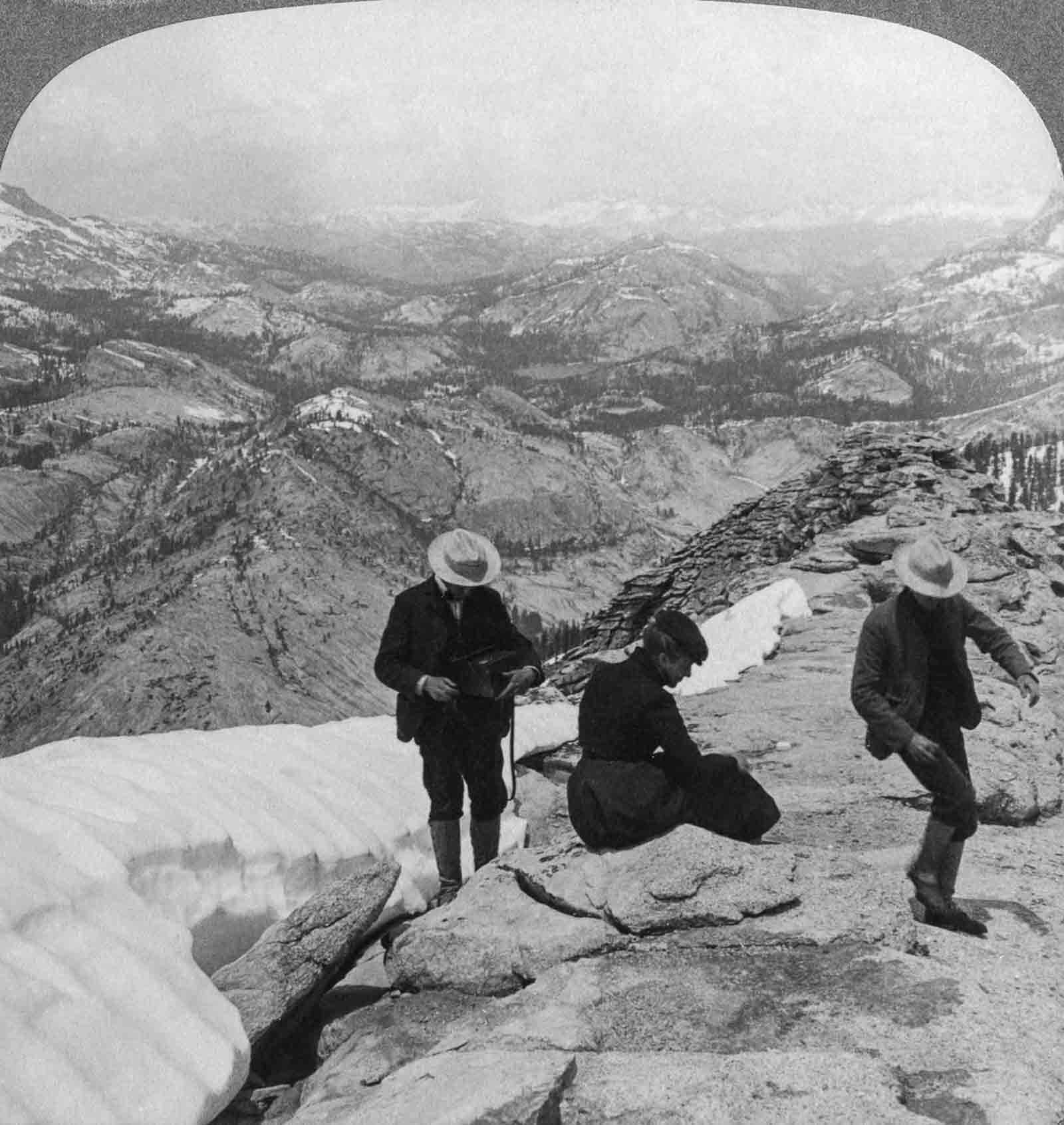

Tourists look from Clouds Rest over the Little Yosemite Valley to Mount Clark. 1902.

Tourists on Clouds Rest in Yosemite. 1902.

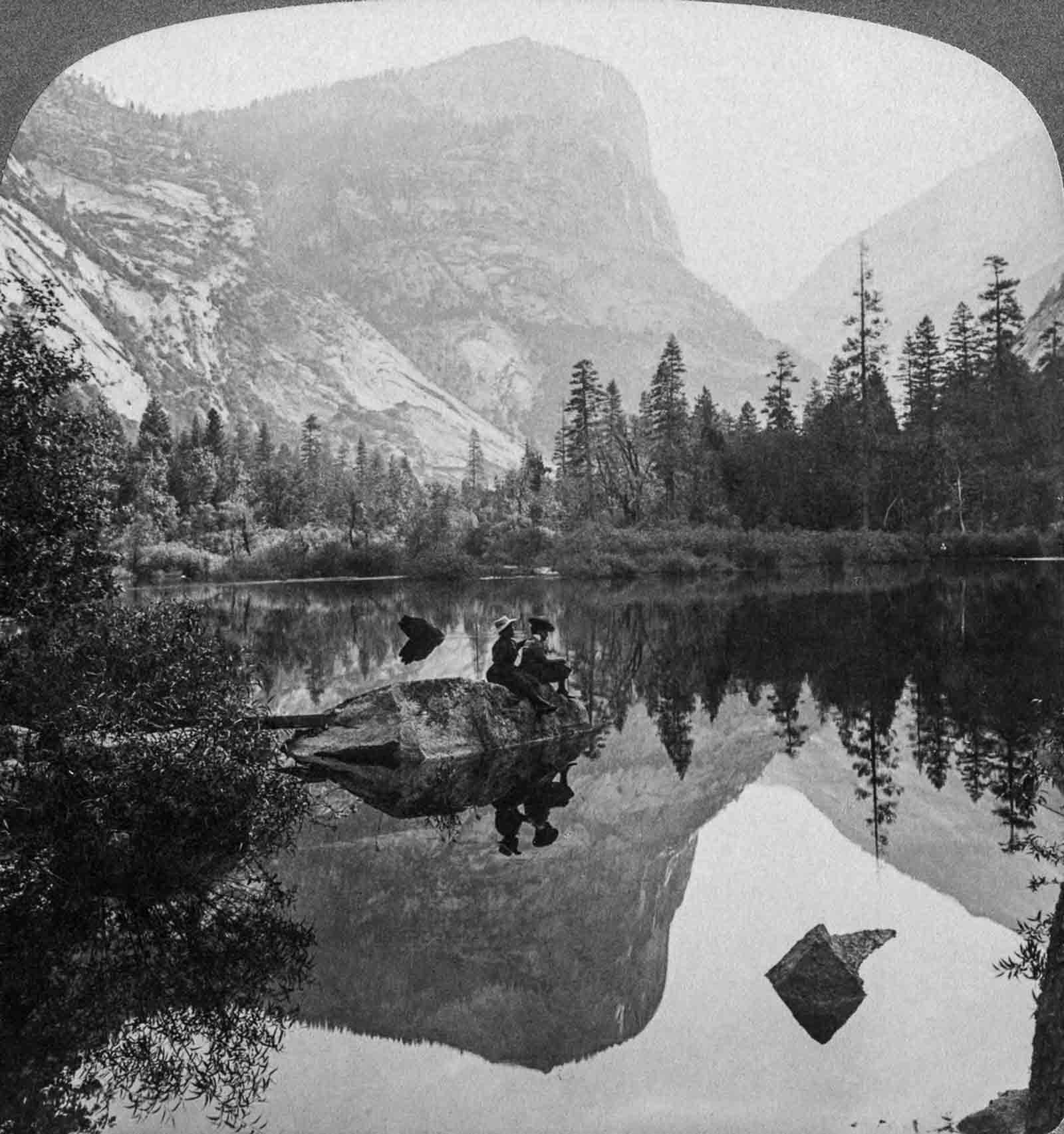

Tourists at Mirror Lake in Yosemite. 1902.

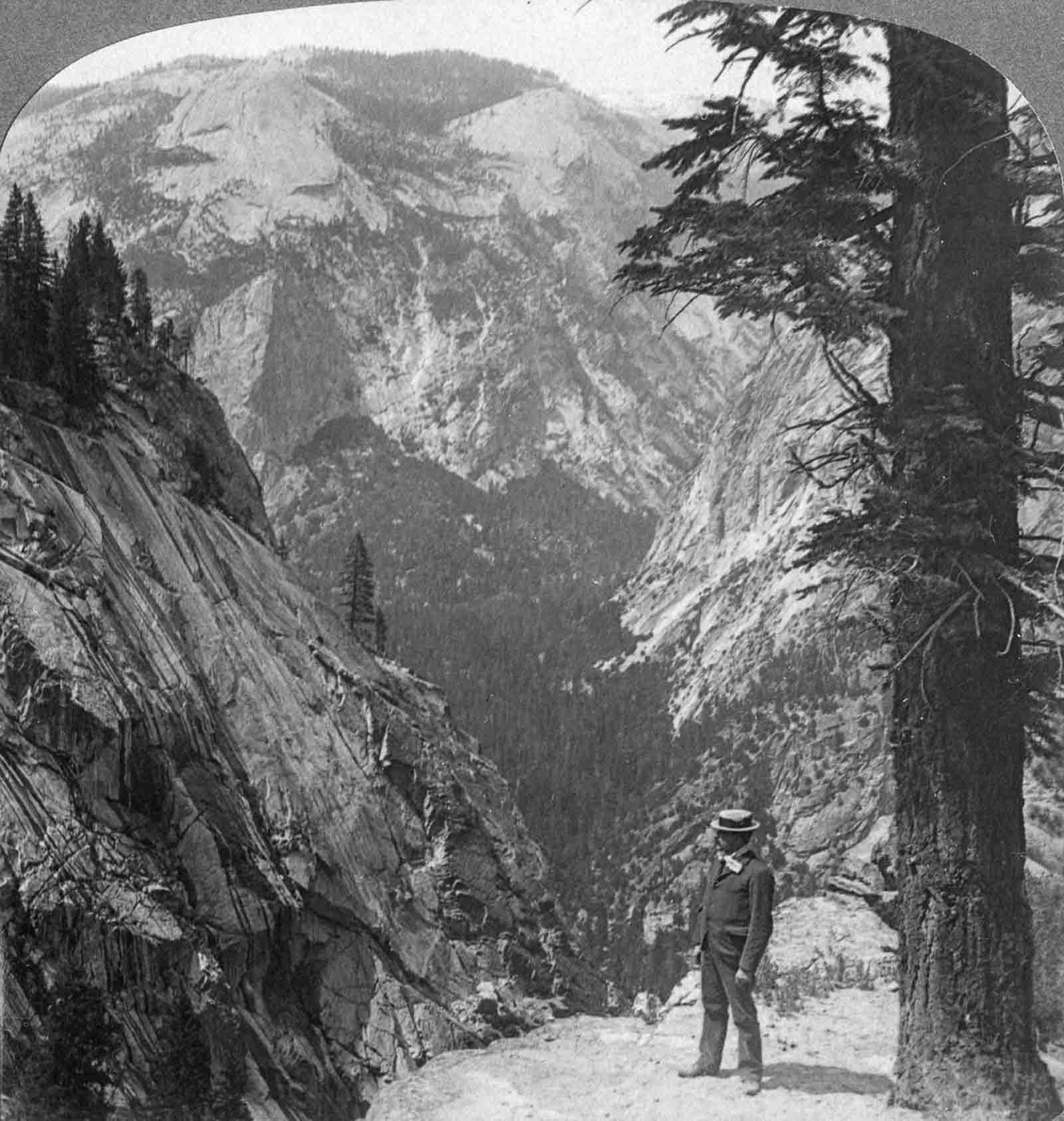

A tourist looks out over the Yosemite Valley. 1902.

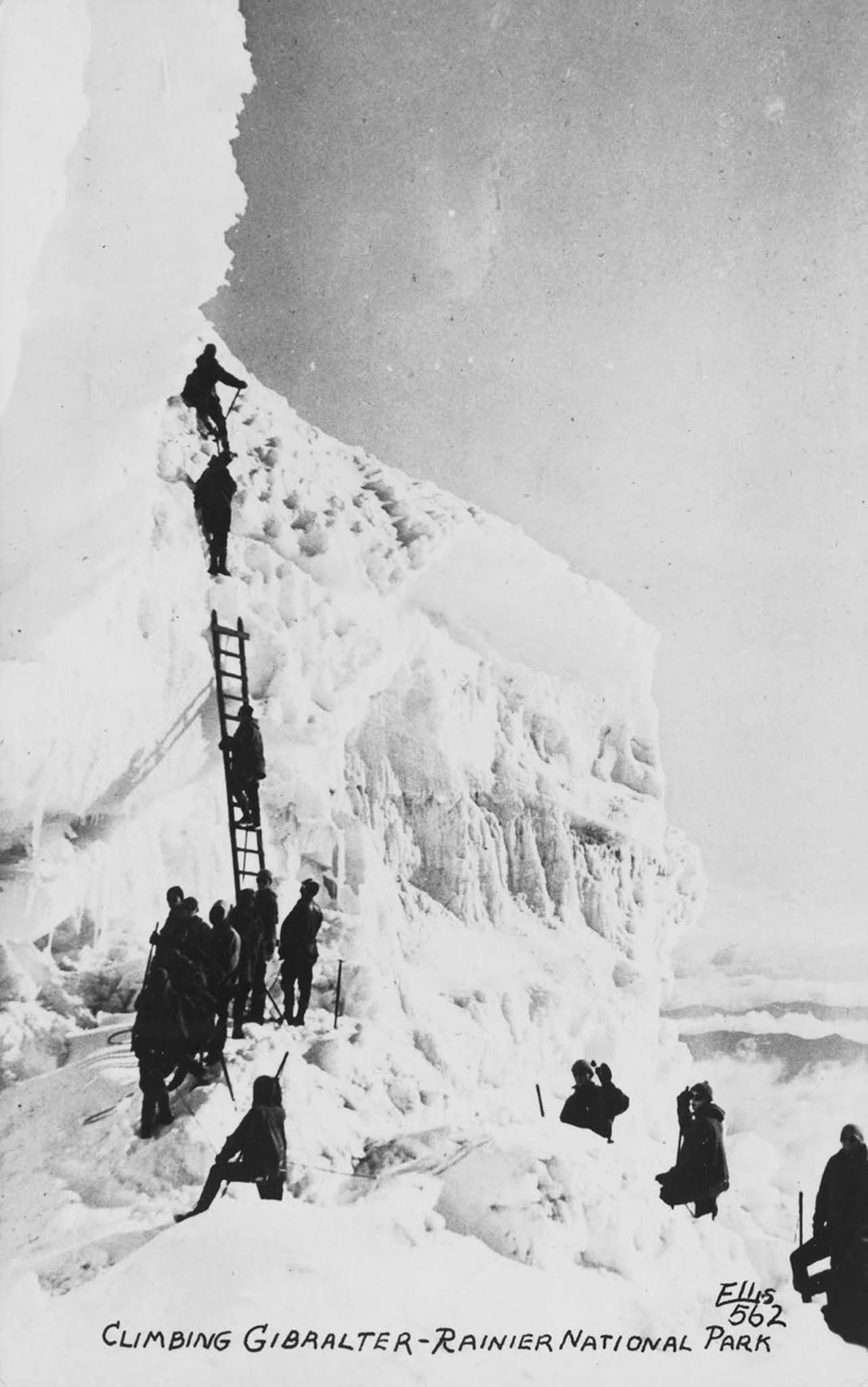

Climbers scale Mt. Rainier. 1910.

A man stands behind the “Pulpit Terrace” formation at the Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone. 1904.

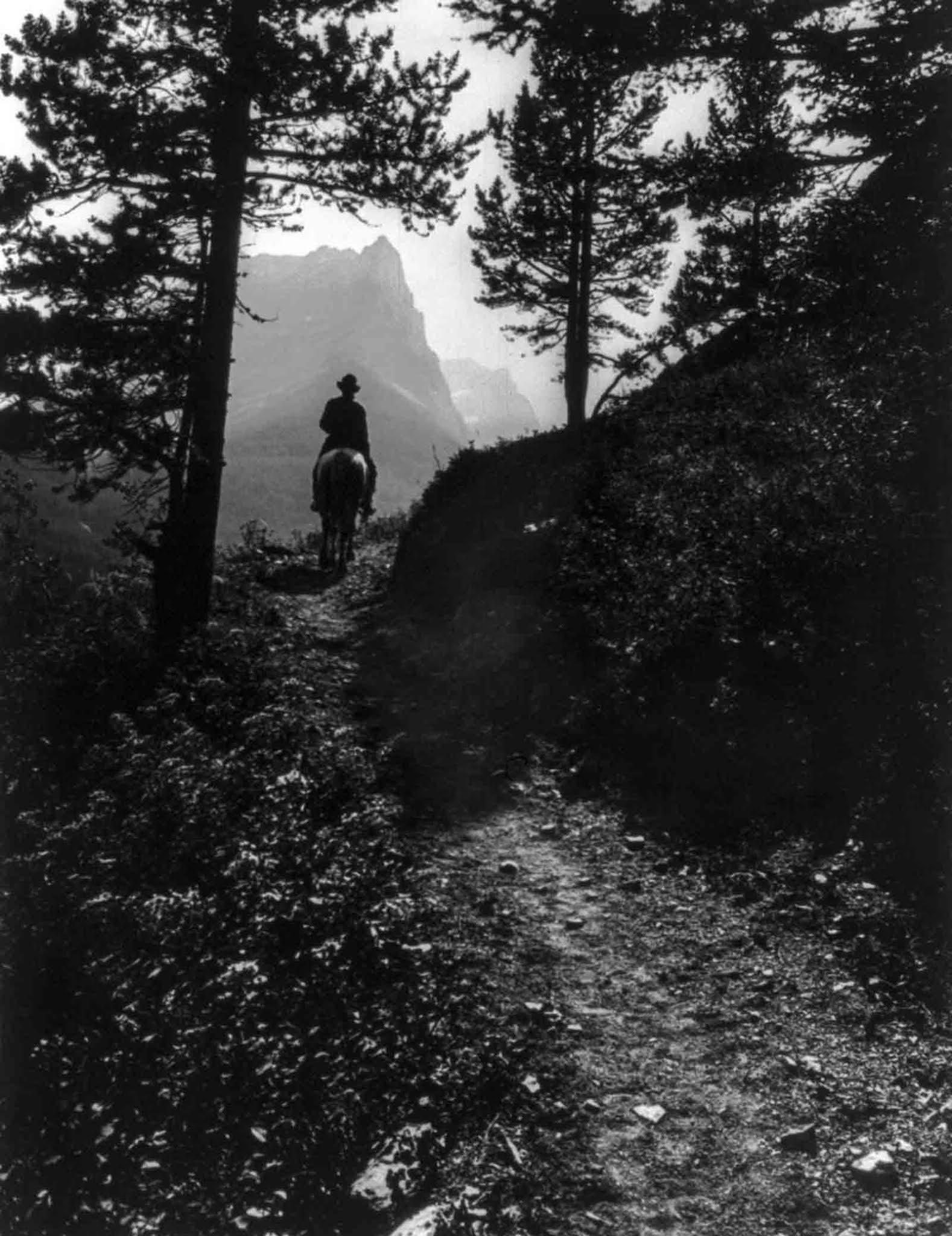

A rider on a trail at Glacier National Park. 1916.

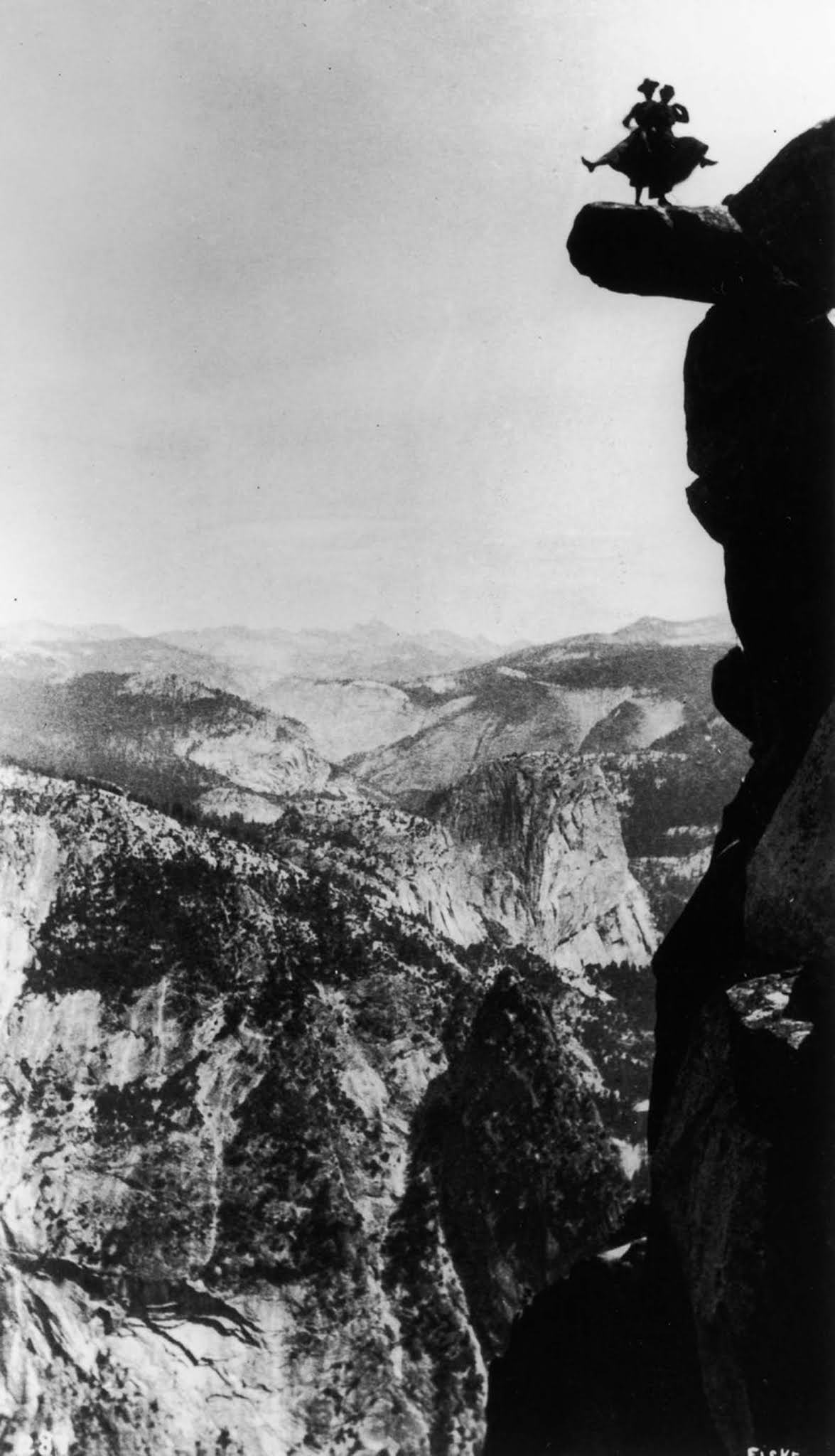

Kitty Tatch and friend dance on the overhanging rock at Glacier Point in Yosemite.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Corbis / Getty Images / Article based on America’s National Park System by Lary M. Dilsaver).