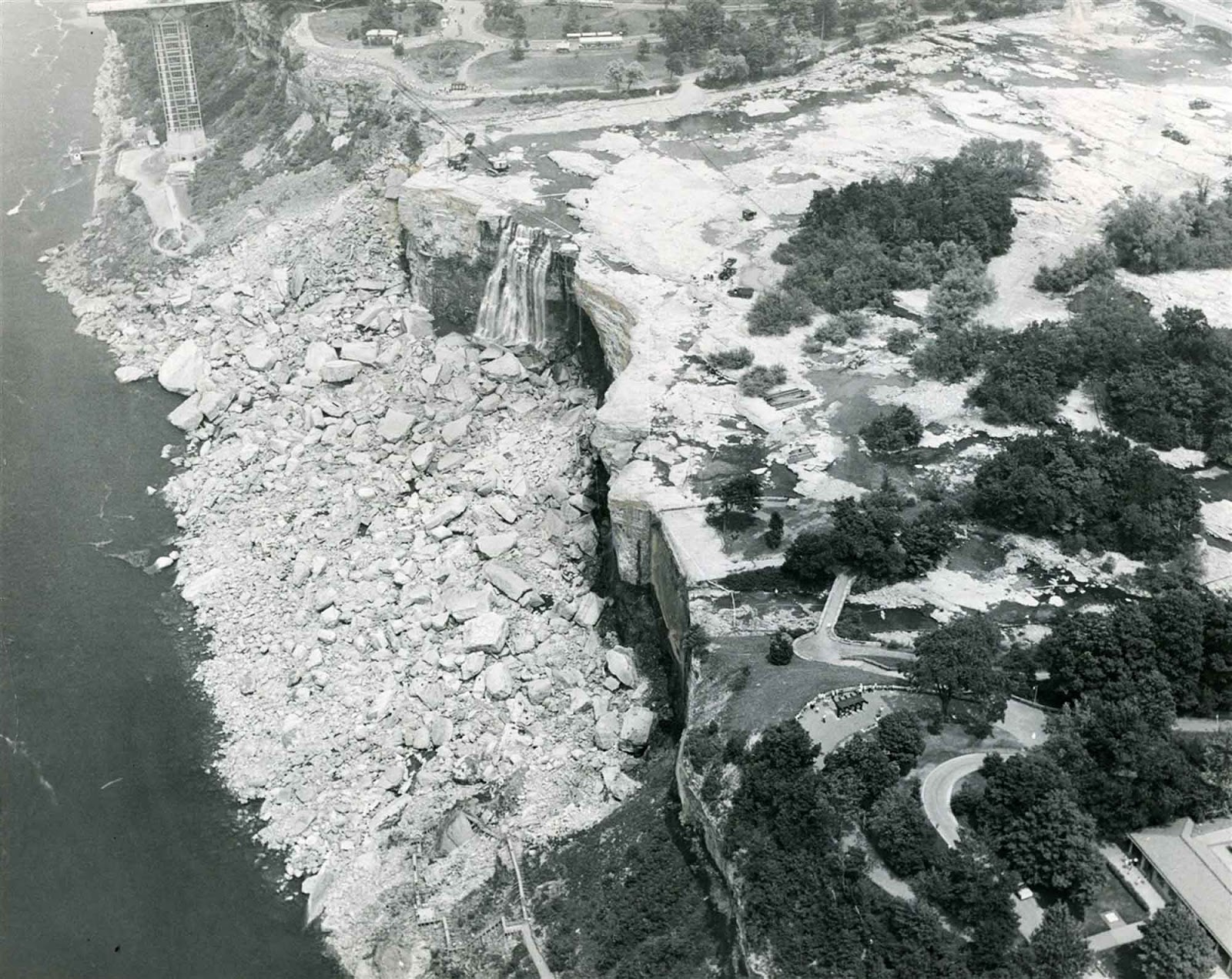

For six months in the summer and fall of 1969, Niagara’s American Falls were “de-watered”, as the Army Corps of Engineers conducted a geological survey of the falls’ rock face, concerned that it was becoming destabilized by erosion. These stark images reveal North America’s iconic – and most powerful – waterfall to be almost as dry as a desert.

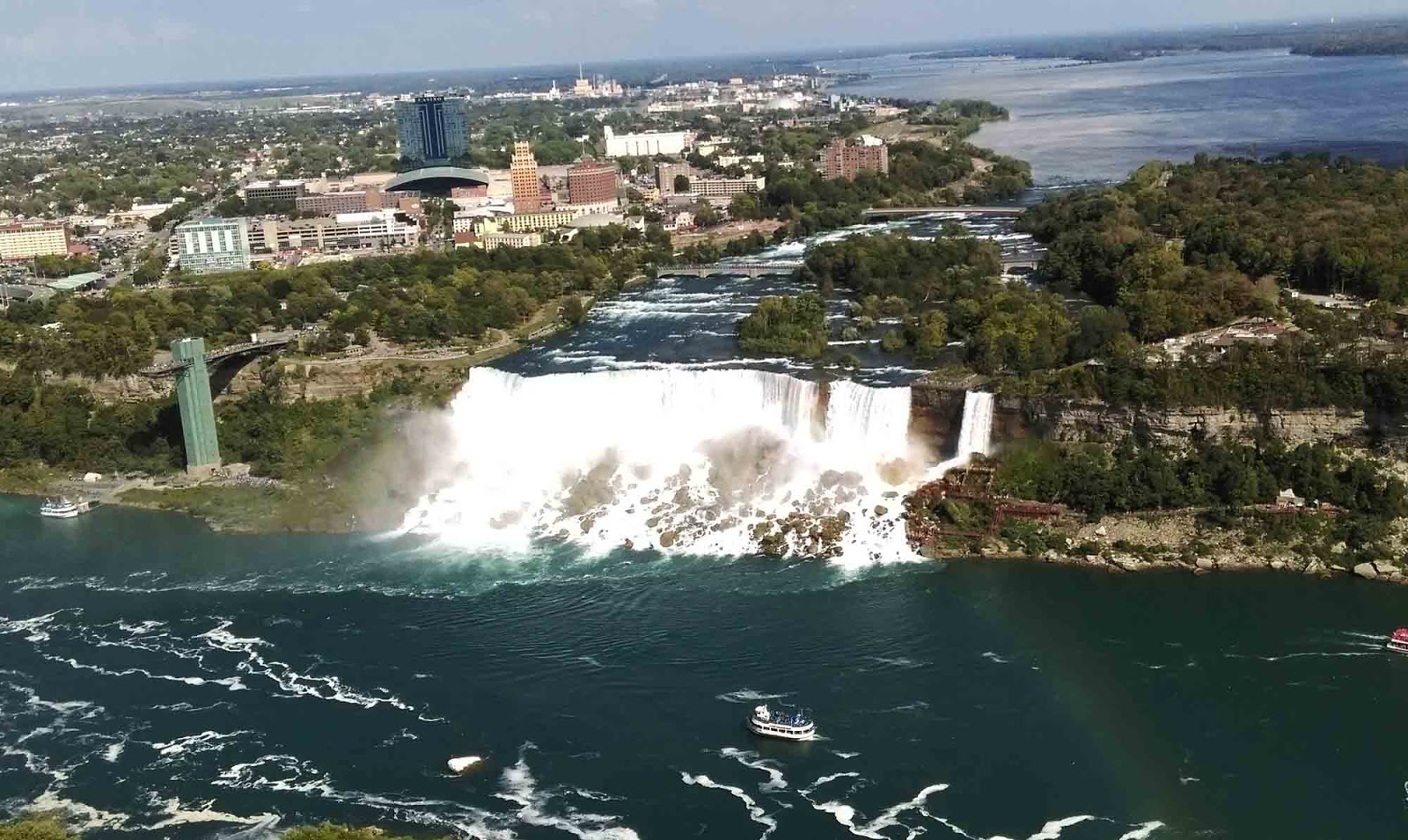

Niagara Falls is the collective name for three waterfalls that straddle the international border between Canada and the United States. From largest to smallest, the three waterfalls are the Horseshoe Falls, the American Falls and the Bridal Veil Falls.

The Horseshoe Falls lie mostly on the Canadian side and the American Falls entirely on the American side, separated by Goat Island. The smaller Bridal Veil Falls are also on the American side, separated from the other waterfalls by Luna Island.

The riverbed was crisscrossed with a series of cracks that were being examined for possible links to rockslides.

While the Horseshoe Falls absorbed the extra flow, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the riverbed and mechanically bolted and strengthened any faults they found.

To dewater the Niagara’s American Falls the army had to build a 600ft (182 m) dam across the Niagara River, which meant that 60,000 gallons of water that flowed every second was diverted over the larger Horseshoe Falls which flow entirely on the Canadian side of the border.

The dam itself consisted of 27,800 tons of rock, and on June 12, 1969, after flowing continuously for over 12,000 years, the American Falls stopped. The completed dewatering of the American Falls was made easier because only 10% of the water follows that route.

While the Horseshoe Falls absorbed the extra flow, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the riverbed and mechanically bolted and strengthened any faults they found; faults that would, if left untreated, have hastened the retreat of the American Falls. A plan to remove the huge mound of talus deposited in 1954 was abandoned because of the high cost.

For a portion of that period, while workers cleaned the former river-bottom of unwanted mosses and drilled test-cores in search of instabilities, a temporary walkway was installed a mere twenty feet from the edge of the dry falls, and tourists were able to explore this otherwise inaccessible and hostile landscape.

During this time, two bodies were removed from under the falls, including a man who had been seen jumping over the falls, and the body of a woman, which was discovered once the falls dried.

Two rockslides from the plate of the falls in 1931 and 1954 had caused a large amount of rock to be collected at the base.

Finally, in November 1969 in front of 2,650 onlookers, the temporary dam was dynamited, restoring flow to the American Falls.

Even after these undertakings, Luna Island, the small piece of land between the main waterfall and the Bridal Veil, remained off-limits to the public for years owing to fears that it was unstable and could collapse into the gorge.

The Niagara’s American Falls. (Picture taken in 2016).

The falls—American Falls, Horseshoe Falls, and the small Bridal Veil Falls—formed some 12,000 years ago when water from Lake Erie carved a channel to Lake Ontario.

The name Niagara came from “Onguiaahra,” as the area was known in the language of the Iroquois people who settled there originally. After the French explorer, Samuel de Champlain described the falls in 1604, word of the magnificent sight spread through Europe.

A visit to Niagara Falls was practically a religious experience. “When I felt how near to my Creator I was standing,” Charles Dickens wrote in 1842, “the first effect, and the enduring one—instant lasting—of the tremendous spectacle, was Peace.”

Alexis de Tocqueville described a “profound and terrifying obscurity” on his visit in 1831, but he also recognized that the falls were not as invincible as they seemed. “Hasten,” Tocqueville urged a friend in a letter, or “your Niagara will have been spoiled for you.”

Today, erosion of the American Falls is estimated at 3 – 4 inches every 10 years (used to be on average 4 feet a year). The water flow which is regulated at a minimum level of 10% of the estimated 100,000 cubic feet per second during the summer (50,000 cubic feet per second during winter) is insufficient to cause major erosion.

Do you know about the daredevils who go over the Niagara Falls in barrels? Take a look at these pictures.

(Photo credit: Niagara Foundation / Niagara Frontier / Smithsonian Magazine)